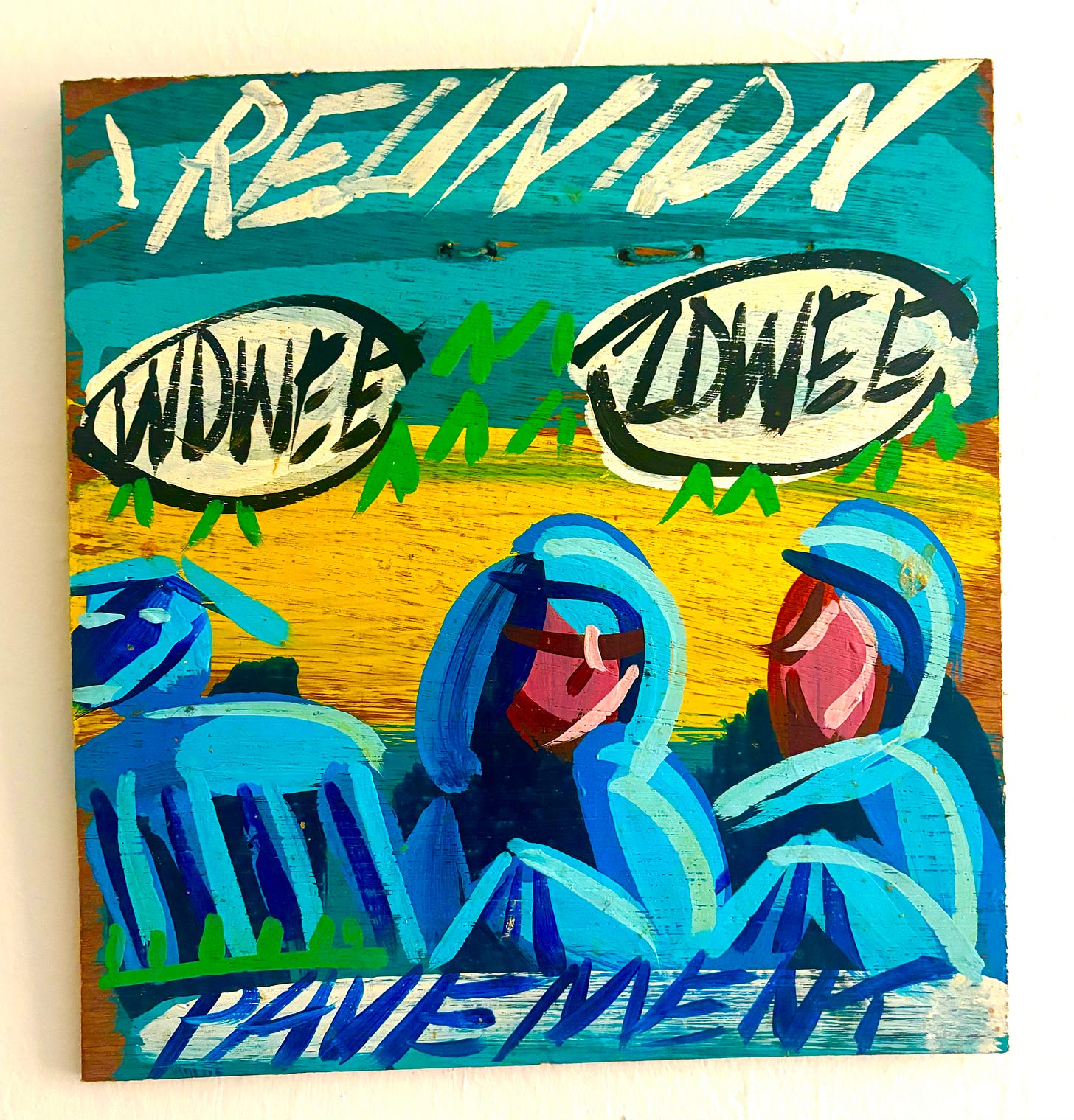

This week marks the 30th anniversary of Pavement’s third album, Wowee Zowee. It’s a tight race, but it’s my favorite Pavement record, which I think by default makes it my favorite album by anyone. It’s an album I know very deeply but still find somewhat mysterious. I’m always finding new nuances in its sprawl. Here are some things from my archives I’ve written about Wowee Zowee over the years, going alllllll the way back to when I was 15.

I wrote this tangent about Wowee Zowee in a post about a mix CD I made in September 2006:

In a way, I was mimicing the internal logic of Wowee Zowee, which is the only album in the Pavement/Malkmus catalog not to be obviously sequenced as an even set of sides. In its vinyl incarnation, Wowee Zowee is split over three sides, with side d left blank. The way the songs are divided over the sides do not make the same obvious, intuitive sense as the other LPs in Malkmus’ discography, and it’s not much more graceful on the cassette edition of the album, which breaks the sequence in two between “Best Friend’s Arm” and “Grave Architecture.” On cd, the record makes a great deal more sense. Rather than follow the conventional wisdom of George Martin and The Beatles (album sides should begin and end with key selections, weaker tracks should be shuffled between highlights) or the record industry (the most obviously likeable songs should be frontloaded and the lead single should be either the first or third song on the first side), Wowee Zowee places its emphasis on its sprawling center. If any point can be gleaned from the album at all, it may be in finding the beauty and pleasures of life’s lengthy, often mundane middle act.

Contrary to the claim of its initial detractors, Wowee Zowee is by no means shapeless. It has a brilliant, if fairly unconventional opening, and progresses toward dramatic heights in its final third (“Fight This Generation” –> “Kennel District” –> “Pueblo”) before reaching its climax (“OhhhmyyyyyygaaaaahdIcan’tbelieveI’mstillgoing!!!!”), and ends with a brief epilogue in the form of “Western Homes,” which is horribly underrated and totally necessary as a light-hearted postscript to the unhinged grand finale of “Half A Canyon.” Without the artificial structure of the vinyl lp, Wowee Zowee‘s flow is more cinematic, and that’s part of its nearly infinite charm.

I wrote this about an alternate version of “Black Out” back in December 2006:

For most (if not all) of the tour for Crooked Rain, Crooked Rain, “Black Out” was included on setlists as “New Gold Soundz,” which is fair enough given its general vibe, though this early draft is more along the lines of “New Stop Breathin’.” Interestingly, with its original chorus (which incidentally repurposes the lyric “haunt you down,” and makes me wonder whether or not this was recorded before or after the “Haunt You Down” 7″) the song takes on an accusing, wounded tone whereas the final version is notable for its contented aimlessness. Several lines that made it to the finished recording appear in a slightly negative variation — “your own hall of shame,” for example — and the implication of “the lessons you’re learning” shift over to a darker sort of self-revelation. Malkmus’ voice couldn’t quite handle the demands of his own arrangement (though I think he could probably do okay with this now that he’s grown into a more confident vocalist), but I would kinda love to hear someone with a full, commanding voice take on this version of the song.

This is a post about “Pueblo,” one of my favorite songs on the record, from March 2012.

Pavement “Pueblo” (Live in Cologne, 1996)

Pavement is known for having very smart and clever lyrics, but most of the lyrics on Wowee Zowee are incomplete, improvised or outright gibberish. A lot of the lines that are clear are bits of evocative language that stuck at some point in the creative process, particularly in the numbers that were staples of the band’s live set before they were tracked in the studio. The record is in some ways improved by this impressionistic quality, amplifying moments of absurdity and adding a touch of mystery to emotional peaks, such as the climax of “Pueblo.” That section may be the most devastating thing Stephen Malkmus has ever written, as he returns from a desolate instrumental section by rising up with a ragged, surprisingly vulnerable “when you move, you don’t move, you don’t mooooove.” The verses suggest some kind of dramatic context, but I have no idea what this particular bit of verbiage means or what it has to do with a guy called Jacob. Nevertheless, it hits me in the gut like few other pieces of music. I know this feeling, this abstract thing that has resonated with me for over half of my life, and that it feels something like giving up something that you want so badly it stings. Malkmus is very rarely a guy who spells out the emotional content of his music, and this song is a good reason why he shouldn’t need to bother – when you can strike this chord, provoke this sort of complex emotional response, why would you ever need to be so literal?

Here’s a post I wrote about “Grounded” after seeing Pavement perform it in Central Park in 2010.

Pavement “Grounded” [Live in London, 4/11/1997]

Every time they played “Grounded”, I did this thing when that huge, majestic riff comes in — tilt my head back, get up on my tiptoes as it ascended, and then “crashed” down as the motif ended with Steve West’s drum fill. It felt like the right response, it had just the right physical and emotional resonance. I will maintain forever that Wowee Zowee would’ve sold a lot more copies if “Grounded” was the lead single. Pavement’s singles erred on the side of the sillier, more novel tunes, but I think 1995 was the right time to remind listeners that the band had a darker, more emotional side, and could write this ambiguous yet totally devastating ballad about the inner life of some patrician doctor. It certainly would’ve made more sense on the alt-rock radio of that time than anything else on the record. (Would any other Pavement song make sense coming after “Glycerine”?) All these years later, it’s taken its rightful place among the band’s best-loved classics, a cornerstone of the reunion tour setlist. Most of Pavement’s best live songs are due to the energy level or opportunities for improvisation, but with “Grounded,” it’s just about the song’s intensity. It has an unusual and beautiful power.

This is a video treatment for "Grounded" I wrote for a one-off Pavement zine called Four Channel Destiny circa 1998, which compiled by Becky Rifkin. Most of it was repurposed writing from the disc.server Pavement Message Board, which as basically my first exposure to the internet. I’m still friends with some of those PMB/Fake Matador Bulletin Board people today! I was around 18 when I wrote this.

All black and white, same film and exposure as the movie Clerks. NO JUMPCUTTING!!! First part (over the intro up until the vocal comes in) in an operating room, a group of surgeons are performing some form of routine surgery on some guy) SM is one of the doctors. The surgery scene ends and SM walks into the hallway and as the vocal comes in he begins to lip synch along. He looks weary and bored, and very depressed as the verse progresses we see Dr. Malkmus stop into his office to speak to his receptionist, and change to his civilian clothing and goes out to the park lot to that new sedan he bought. We see SM in a traffic jam. Over the guitar riff we see SM hamming up the despair and sadness in his car. As the next verse comes in, we see SM arrive at his house. We see his preppy upper middle class family. SM is tired and kind of ignores them as the guitar riff comes in again we see SM and his "wife" being affectionate, but they are clearly disgusted with one another and begin to fight. We see SM back at work the next day, and the video ends the way it began.

Going back even further in time, this is my review of Wowee Zowee for my tiny high school's newspaper in the spring of 1995. I'm not sure how to feel about my writing then being not a lot different from how I write today. Wowee Zowee is probably my favorite record by anyone, but I hedged on that star rating like I was getting ready to dial down my enthusiasm in Pitchfork reviews years later.

Speaking of Pitchfork, here’s an excerpt of my 10.0 review of their 2010 greatest hits album Quarantine the Past that I believe gets to the core of why Pavement has resonated with me so deeply through my life.

Malkmus' lyrics, central to the band's appeal, alternate between whimsical nonsense and epigrammatic quotables. The songs seldom slot neatly into readily identifiable emotional states or refer to specific experiences, instead falling into the liminal spaces between thoughts and feelings. Malkmus' words indicate context and supply the listener with rich imagery, but the real poetry is in the way his phrases flow with the melodies, and are offset by evocative guitar textures and unexpected noises. The group never compromised tunefulness for artiness, but mystique and abstraction were among their core values. In retrospect, certain lines ring out like statements of intent-- "We need secrets," "Tricks are everything to me."

The very best Pavement songs delight in curiosity and imagination, drawing connections between images and ideas as if everything in the world was full of character and significance. This is part of why, for example, a playful joke about the voice of Rush's lead singer in "Stereo" never gets stale. It's in the middle of a song that may as well be a sub-genre unto itself, bouncing about gleefully, utterly fascinated by the all the obscure details of the world. They found the magic in the mundane, and could make small enthusiasms, silly in-jokes, and skewed observations seem profound and glorious.

And finally, here’s an excerpt from an interview I did with my old friend Bryan Charles about his Wowee Zowee book in the 33 1/3 series.

Right, Billy Corgan is kinda like the villain of your Wowee Zowee book in a way, always turning up to foil Pavement’s plans or cast Malkmus in sharp relief. I like that about the book. He’s such a fascinating figure. He’s so frustrating, but I think that makes him interesting. A lot of odd psychological depth. The problem of writing about Billy Corgan though is that you’ll have all these superfans calling out for your head!

Bryan Charles: Yeah, but I wouldn’t mind that so much, I guess because I consider myself a super fan in a way. Not of the recent stuff but certainly of the man in his prime. I see him as tragic figure now, sort of like the “Mark Zuckerberg” of The Social Network. That was one of the challenges of writing the Pavement book — and maybe why the other book about them is so bad — there really is no great drama there, no story. The story is basically this semi-genius from California got together with his buddies and made a handful of records, most of them in just a couple of weeks. There’s only so much you can say about that, especially when the semi-genius in question has no great interest in ballyhooing his achievements. So part of the story of Wowee Zowee is me actually trying to figure out what the story is and then writing the book. I know some people didn’t dig that, or thought it was half-baked or whatever. But Pavement, more than most bands I can think of, really resist interpretation. They’re such great guys, and as you’ve pointed out, all really interesting personalities, but what they do together is surprisingly hard to explain.