Fluxblog 539: Interviews with Deerhunter

Conversations with Bradford Cox from 2011, 2013, and 2015

Do you miss Deerhunter? I certainly do. Bradford Cox hasn’t released new music since Deerhunter’s most recent record Why Hasn't Everything Already Disappeared? came out in 2019. It’s funny how a guy who used to be arguably overly prolific has shifted into D’Angelo/My Bloody Valentine mode.

I’ve been lucky enough to interview Bradford three times, and he’s an incredible interview subject – extremely open, unafraid of talking shit, thoughtful about his art, and extremely enthusiastic about other artists’ work. The first interview was published by Rolling Stone, the other two interviews were published by BuzzFeed. Here they are in the same place for the first time.

November 7 2011

Bradford Cox Talks Nervous Breakdown, New Atlas Sound Album

Bradford Cox has spent the past half-decade building one of the most acclaimed bodies of work in indie rock. A prolific songwriter, Cox has released dozens of songs on his own as Atlas Sound, and many more as the frontman of Deerhunter. Parallax, his latest album as Atlas Sound, hits stores tomorrow. The disc, which contrasts some of his most pop-oriented tunes to date alongside more abstract digressions, was recorded earlier this year before the singer suffered a nervous breakdown while on tour with Deerhunter. In this conversation with Rolling Stone, Cox opens up about his creative process and laments a lack of queerness in contemporary rock.

The last time I saw you play live, it was a Deerhunter show at Webster Hall, and you were dressed up in the teen idol look that you have on the cover of Parallax. What inspired this look?

It’s nothing more than a junk-shop version, a thrift store version of Ricky Nelson or something, but emaciated. It’s nothing new. I’d been really yearning for there to be some icons in music, in the kind of music I’m interested in lately, because it’s fucking dismal, what’s going on right now.

In terms of charismatic figures?

Hetero-centric, boring, scruffy 20 year-olds are ruining the fucking face of rock and roll, you know? There are no Patti Smiths or Joey Ramones, or Lou Reeds, even. Well, but Lou Reed is fucking playing with Metallica, whatever. There needs to be some vital something, and I mean, I’d like to try to be that, if possible, if I may be so bold.

What’s missing?

Queerness. Homo-eroticism, boyhood.

In the Eighties, there were a fair number of, if not out, but queer artists who actually became rock stars. But it’s very hard to come up with many people in the past decade or so who fit that niche.

I’ll raise my hand.

Why do you think this has been absent from a lot of music?

I think that the world seems to be in some sort of conservative, cultural, retroactive, retrograde… I don’t know. It’s not that I think being queer is something someone should aspire to. People should just be themselves. I just don’t see a lot of selves, I just see a lot of… I don’t know, I just don’t want to be hateful. I don’t see a lot I can relate to. I’d be real disappointed if I was 17 or 16 or 15 or 12 or 11, you know?

So when you were that age, which wasn’t all that long ago, who inspired you?

Joey Ramone, Patti Smith, Lou Reed’s image, whether it was fucking real or not, I don’t know. The B-52s, Elvis, the Everly Brothers. Not exactly the queerest thing in the world.

Is there something in the music that you’re making, particularly on Parallax, that you’ve been trying to push to the foreground of what you do?

Sexuality? I don’t hide anything, but I also don’t really highlight anything either. For a long time I just said I was asexual, but now I just realized that… I’m still, I guess… I mean, I’m queer. I just sort of, don’t really have a very big self-esteem, so asexuality is sort of like a comfort zone where you don’t get rejected. So maybe that stuff is bubbling up, I don’t know. I don’t intend my music to be about that. I intend my music to be kind of cosmic.

You’re very prolific. How do you work to curate your own body of work? When do you know that a song like “Mona Lisa,” which you had released as a demo on your blog, was something you should go back and rework?

Oh man, it’s kind of like my bedroom, you know? It’s just a mess. It’s just all this shit everywhere. But like, there’ll be one thing in the corner of the room, one object, in a pile of objects, it just sort of gets seen more. You know what I mean? My body of work, I guess, is just a lot of strips and scraps and stuff. “Mona Lisa,” it’s not even a song that means that much to me. I can’t explain why. It fit in that part of the album. I needed something. I feel like “Modern Aquatic Nightsongs” is a pretty desperate and dark expression of something. It really goes into this abyss, you know, at the end of that song, and I’m just like I don’t want to go from one abyss into like, the “Doldrums,” which is another abyss. The idea is to just sit there and throw out life rafts every once in a while.

When you have all of these songs, how do you form connections with one instead of another?

Well, the same process that the audience does. I’m basically the audience for my own music. Because I don’t write things consciously. I don’t set out to write things, it’s all automatic writing, like the music and the chords and the lyrics and everything. So when I listen to it, I’m sort of analyzing it the same way that somebody who gets the record and listens to it for the first time. Certain things stick out to them, certain things stick out to me when I’m listening to my own stuff, you know?

When you’re working with Andrew VanWyngarden from MGMT on “Mona Lisa,” or with your bandmates in Deerhunter, do they help you edit?

I usually sequence things in my mind. I’m really big on narratives. Sometimes I can be a little bit difficult with it, like Halcyon Digest, I understand the problem a lot of people had with the sequencing of that album.

Explain that.

If I handed a bunch of songs to a record label and said “Hey, here’s 12 new songs. Sequence them, make an album, do the artwork for me,” it would be totally different. It would be top-loaded, start out catchy. I’m just not interested in that. The records that have always struck me are ones that I hated the first time I heard them. I was listening to Lou Reed’s The Blue Mask with my friend yesterday and enjoying it, and all of a sudden this song comes on, “I love women, I love all kinds of women, women, women,” and I’m just like “Fuck!” and I literally ripped the needle off the record, I was just like, “Fuck this shit.”

You recorded Parallax this summer. Is it strange that it’s taking so long to reach people?

It is, especially because a lot of stuff has happened to me personally, which I don’t really care to go into. In between the making of this record and where I’m at now, it’s hard for me to put myself back. I want to be able to go back to that place so that I can fully express all the ideas that were present when I was making the record. But now, it seems a little bit faded. I might as well have recorded the record ten years ago. I don’t feel the same way. I was really comfortable and lonely simultaneously when I made this record.

That sounds kind of peaceful.

Yeah, people keep referring to confidence and stuff. I felt like an alien that was okay with distance.

Is that why you worked with the photographer Mick Rock for the cover of Parallax? He worked with David Bowie on similar themes.

I really don’t mean to play up the Bowie thing. Because I’m not Bowie. I mean, I relate to a lot of the anxiety I think Bowie went through as a person. But Bowie was a very sexual and very… I’m not that.

There’s a similar resonance between what you’re projecting on this record and the Bowie of The Man Who Fell to Earth.

Yeah, that’s exactly what the record is. I mean it is. I guess it’s my revision of that mythos. With my own bullshit emotional baggage shoved in there.

Are you working on a new record right now?

I’m writing for the next Deerhunter record. I’m trying to. I’ve got a lot of personal stuff that’s absorbed all of my consciousness. Specifically, a personal thing. A confusion. A confusion!

When you go through periods like this where you’re just kind of absorbed in a personal thing, how does that effect your writing?

Well, I never have before. I’ve been nothing but the guy on stage that you see on the Internet. I think everything started to happen when I was in Australia and gave an interview on the radio and they filmed it and I was just going through a really hard time. And then everybody made fun of me and was like, “Oh, look at this whiney cocksucker.”

What were you talking about in that interview?

Being unsatisfied and maybe I was trying to talk about being lonely or something. They made it out that I was some whiney rock star. My incredibly glamorous life is not enough to keep me from whining. You know, people say “Man, I’d kill to be doing what he’s doing, and he’s complaining?” I’m so grateful for all the things I get to do. I’m very happy with whatever amount of success I’ve had. But it doesn’t keep you warm at night. And, I started to get really worn down. And then they say, “You’ve got to do more, you’ve got to go here, you’ve got to go there. Be ready to get picked up at the airport tomorrow.”

It’s all about parallax, man. Five years for one person is 20 for another, you know? It’s like, if a car is coming towards you down a highway and you’re going towards it, it’s like this distortion of how fast things go by. And I guess my time as a musician has gone by so fast that I realized that I have no personal life. The other guys in Deerhunter, they all found things. And I just have monomania. I always will. I’m obsessive about one thing, that there’s one thing that’s going to make me happy and it’s making music, or there’s one thing that’s going to make me happy and it’s this person. The music seemed to be the one thing that kept me going and then I was just bound to have this nervous breakdown. And it wasn’t super-dramatic, like in some sort of typical, rock star way or something. It was more pathetic and I sort of had a nervous breakdown in this hotel lobby in London.

After Parallax was recorded, I was forced to go back and do more Deerhunter shows. And I didn’t want to, necessarily, because my mind was in the zone of the new songs. And I had to go back to the Halcyon Digest and Deerhunter songs. There’s nothing in the world I love more than my family, my brothers, the band, the Deerhunter boys. They are absolutely my family. I’ve already been around the planet, like, three time, this year. It’s great for frequent flier miles, but it’s hard on the mind and body, and I just lost it. And when you don’t have someone to call at home. I mean, your mom and your dad, your family is one thing. But it’s not the same. When you don’t feel like there’s somebody that misses you. I am the man that fell to earth in some ways. I don’t have a connection to anyone, besides my family, who love me very much.

Do you think maybe that you’re getting something out of performing that’s kind of a substitute for what you might not be getting from a particular person?

Absolutely. Yes. For sure. Completely. But it doesn’t work. I wouldn’t give it up for anybody. I’ll be lonely for the rest of my life if I have to. This sounds so fucking 1972 or some shit, but I would sacrifice my own needs for rock and roll. Because I believe in it, and I don’t care what that sounds like. If it sounds like a pretense or some sort of megalomania or some fucking nonsense rock cliché – if you know what it feels like, you’ll understand, and if you don’t, you can write me off, because I don’t really give a fuck. But anyone who knows what it’s like to be naked in front of thousands of people and, like, go into a trance. I go into such trances that I’ve busted my teeth out onstage, shoving a microphone into my mouth. And I didn’t feel anything. It’s intense.

April 4 2013

Deerhunter Really, Really Dislike Morrissey And The Smiths

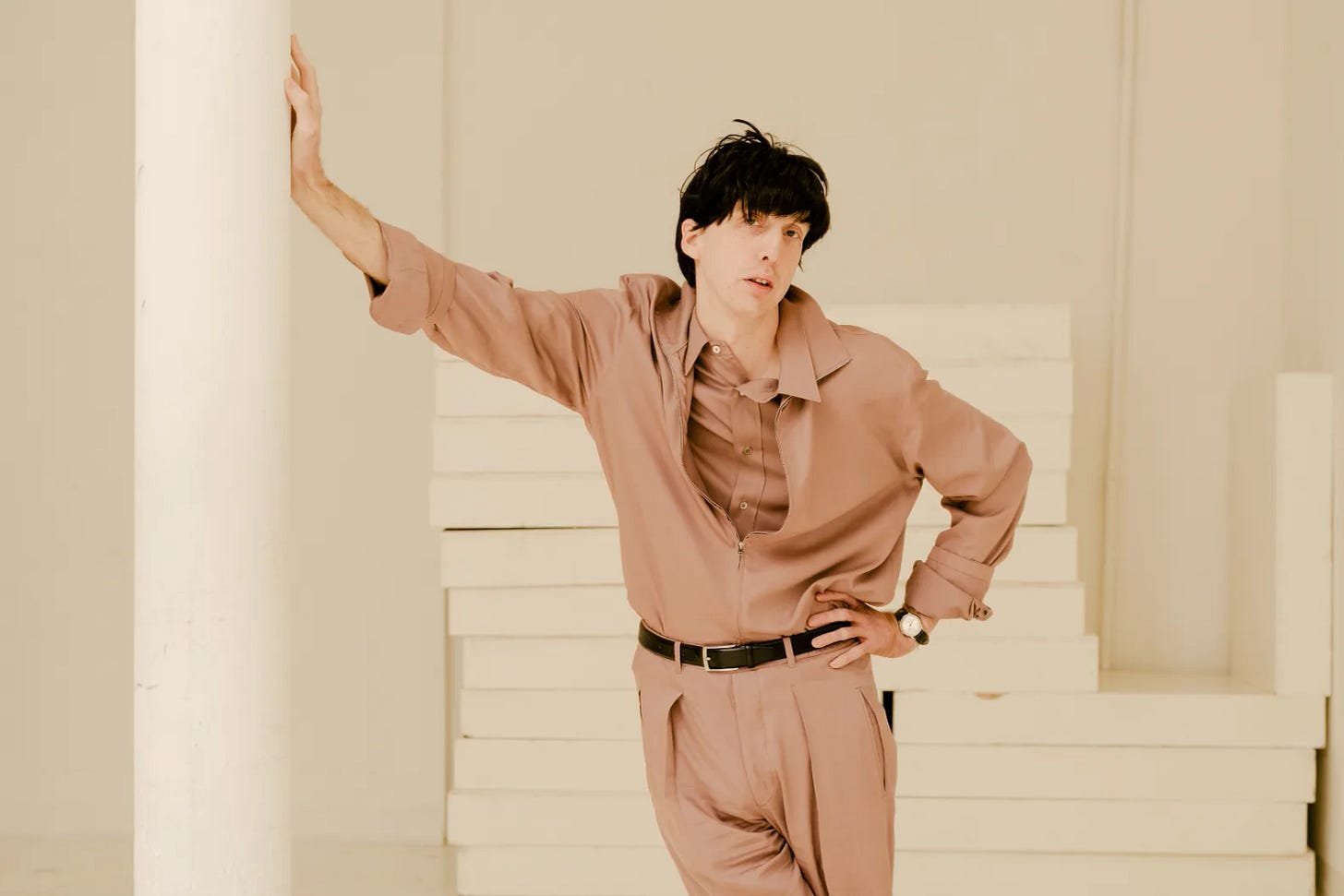

Deerhunter have established themselves as one of the best and most prolific bands in contemporary indie rock over the past half decade. They've been building in popularity with each release going back to their breakthrough LP Cryptograms in 2007 and are poised to reach even more people with their new album Monomania, which will be out on May 7. They premiered the title track from that album this week with a memorable appearance on Late Night with Jimmy Fallon in which band leader Bradford Cox wore a black wig, red lipstick, and bloodied bandages on two of his fingers. Cox, along with his bandmates, chatted with BuzzFeed about why he wore those bandages, his goal of making Deerhunter one of the great American rock bands, and, well, mostly about how much he passionately loathes Morrissey and The Smiths.

When you meet people who don't know your music, what do you say your band is like?

Bradford Cox: I say rock 'n' roll.

Lockett Pundt: Yeah, that's what I say.

BC: Because I don't want to assume too much or too little about anybody's scope of interests. You never know who is into what, you know what I'm saying? You'll meet a mousy dentist and you talk about music and suddenly they're like, "I saw Richard Hell in 1981 at Club 688, which is some dive club in Atlanta at the time. Lockett's dad, for example, he collects guns and I think he's a registered Republican. He's a real man's man, but if you start talking to him, it's all Roxy Music, XTC, Bowie. You can't assume anything about anybody, and especially in the South.

I was wondering because one of my main impressions of your new album was that I kinda wish it was the first one that I'd heard, because it sounds like a good starting point.

BC: Really? In what sense?

In the sense that a lot of my favorite records when I was a teenager were the third, the fifth, the eighth album by someone. It seems like if you were coming into Deerhunter on this record, it'd be…

BC: Cool to go back and investigate?

Yeah, and I think any of the records would've been like that, but this one feels like coming in to R.E.M. around Document.

BC: I can take that as a compliment.

You definitely should, I'm a big R.E.M. fan.

BC: They're one of the greatest American rock 'n' roll bands of all time.

I don't think people appreciate them as much now.

BC: That's because people have short memories. But you know, R.E.M. is a band I think of when I think about Deerhunter. The one thing I aspire to is to be a great American rock 'n' roll band. And when I think of that, I think of Pylon, R.E.M., even bands I don't even particularly like. There's just a lineage, and a history, and a respect for elders. Sonic Youth and things like that, these are bands that paved the way, and none of us would have a job if it weren't for the work they did.

What is the Americanness of it to you, as opposed to being, like, a British band?

BC: There's lots of different ways to answer that question. The Sex Pistols or The Smiths are two bands I don't really care for at all. In fact, one of those two bands I absolutely hate passionately mainly because of their incredibly arrogant singer.

That could go either way!

BC: That did not have an amazing band called Public Image Ltd to save themselves with. God, if I talk about The Smiths and I talk about R.E.M., which do you levitate towards?

R.E.M., no question.

BC: There's a distinctive Americanness about R.E.M., it's a respect for elders. The first thing I ever tell someone when they ask me about my distaste for The Smiths and Morrissey, it's always, well, have you ever read Morrissey's description of The Ramones? If I ever meet that guy…whatever! He makes me want to wear fur. There are Smiths tunes that I find more acceptable than others, but I'd rather just not hear any of them. Frankly, all it took was that one criticism of The Ramones to permanently…you know, if you want to be on that side of the fence, cool.

BC: I will always be on Team Joey, and Team Dee Dee. I come from America, where Bo Diddley was born!

They've got The Beatles.

BC: Yes, they do! And they can keep them. We have Bob Dylan. We have The Everly Brothers.

James Brown.

BC: Jaaaaames Brown! The Beatles, James Brown…I mean, seriously! Anybody who says they dislike The Beatles is a pretentious jerk. Like me. But I actually like them, I like The Beatles. I like all music, really, except The Smiths. Anyway! This is not an article about Morrissey, as much as he'd like it to be, as much as I'm allowing him to permeate the air with his foul and fey musk. His weird, lethargic perfumes.

OK, so you guys were on the Jimmy Fallon show last night wearing some pretty cool costumes. I was genuinely concerned about your hand, because it looked like you had lost a few fingers.

BC: My father had a terrible accident last week, and he sawed off two fingers while woodworking. He was building a bookshelf for my nephew. He's not an amateur, so it was very shocking. And I thought, if my father has to have these wounds and scars and bandages, then so will I, in solidarity. We all love my dad, my dad's a real great American. He's a sweet man and I don't know what I'd do without him. So it was a tribute to my father, who would also hate The Smiths if he ever heard them.

Moses Archuleta: Yeah, it's true.

Are you moving back toward a more theatrical stage show? You had kinda moved away from that on the past couple tours.

BC: Well, theatrical is such a negative word. To me, that sounds so…

Josh Mckay: We were on TV.

BC: If you're on TV and you don't make interesting TV out of it, then you're wasting everyone's time. It doesn't mean you have to make a fool of yourself, like I sometimes choose to do and make a crazy gesture or this or that, but you should at least show a little bit of gratitude for this wild spotlight you find yourself in. So many people try to look so cool, like Morrissey, for example. Or he even refuses to go on TV because he can't control the world, like that Kimmel thing. Because he doesn't agree with someone else, everybody else has to accommodate him. God, Morrissey, honestly! The idea that you're so entitled. What gave them that legacy? What are they, the same size as Bauhaus?

MA: The Smiths?

Yeah, they're definitely bigger than Bauhaus.

BC: Show me numbers!

I think they're about the same level of popularity as The Pixies.

BC: Well, the difference is, Pixies wrote wild albums that challenged the imagination, that mixed science fiction with nautical themes, and The Smiths wrote complaint slips that nobody read. Morrissey's influence is so crippling that it could even deteriorate the flower of modern creative thought. It's like a pungent death shroud over the future and the past.

MA: You know what's funny about this is, we pretty much have never talked about Morrissey ever.

BC: I don't really care about Morrissey.

JM: This is the first time it's ever come up.

BC [to Frankie Broyles, who is scrunching up a cowhide rug with his foot]: Would you stop making this wrinkled? Smooth it out. See, Morrissey would have a fit. If he came into this room and saw this rug, he wouldn't stay at this hotel.

MA: I wonder where there's a vegan hotel.

BC: Well, if they're not vegan, they don't get the astounding honor of hosting…what is it, Sir Morrissey? Order of the British Empire? And isn't he racist?

Yeah, he's had these quotes attributed to him about Asians.

BC: Well, Moses might have something to say about that. Do you have a message for Morrissey?

MA: All I can think of is like, racist things to say. "Hey, Morrissey, me love you long time." But I don't want to fight.

BC: Anyway, let's talk about whatever you want to talk about, Matthew.

I actually came in with very little planned, but you should probably talk a bit about Monomania.

BC: It's definitely better than anything The Smiths ever did. It might not be as good as Vauxhall & I, or whatever the fuck that shit is. I like Johnny Marr's guitar playing occasionally. I like the rhythm section of The Smiths better than any other part of that band.

Those might actually be the people that Morrissey hates most in the world — he's gone out of his way to sue them.

BC: The only Smiths songs I remotely like, the rhythm section makes the song. What's the song, "I haven't got a stitch to wear…?" "This Charming Man," the bass and drums on that song are pretty good, and I think the guitar is pretty good too. Basically everything except the terrible vocals. I should say this, though: There are worse lyricists. I can't think of any. But none come to mind. Can you just imagine The Smiths fronted by Darby Crash [of The Germs]? It might sound a little bit like Deerhunter. I mean, not to say I sound like Darby Crash. His lyrics, honestly, are comparable to, like, Rimbaud.

MA: It's such a good idea. I'm texting Goldenvoice right now, next year's Coachella has got it.

BC: A Darby Crash hologram fronting the rhythm section of The Smiths.

December 3 2015

The Dark Arts Of Bradford Cox

The songwriter behind Deerhunter discusses getting over the trauma of making his band's last record, moving on to a new phase in his career, and what he sees as a lack of vitality in indie music.

Deerhunter's seventh album, Fading Frontier, is the latest entry in one of the most consistently excellent bodies of work in rock music over the past decade or so. The new record isn't a huge departure from what Bradford Cox, Lockett Pundt, and the rest of the Atlanta-based band have done in the past, but much of it has a serene, clear-eyed quality that is distinct from the more depressive or hysterical music in their back catalog. It's the sort of record that is tempting to classify as "mature," but that may imply that the band have lost their vitality, which isn't the case at all.

This is my third interview with Cox, who also records on his own as Atlas Sound. He's a remarkably candid conversationalist, and interviews with him tend to feel more like a heart-to-heart than a purely professional exchange. The first time I talked to him was for an extremely emotional Q&A at Rolling Stone not long after he had what he described as a nervous breakdown. The second time was for BuzzFeed, and it basically amounted to him making fun of Morrissey for a half hour. This time around, he spoke very openly about this new phase of his career, his alienation from the current indie rock scene, and what he calls the "dark arts."

My impression of the new record is that it feels like the calm after a storm, or like coming out of some period of intense emotion. Like coming out of depression, and not necessarily feeling happy, but just knowing you're on the other side of it. Is that at all what you were going for?

Bradford Cox: Fading Frontier was recorded mostly in the daytime, and we were always in this garden behind the studio. It was that perfect time of spring, when it's not that humid. It's cool at night, warm during the day, and lots of blue skies. Once summer rolls around in Atlanta, it becomes gray, humid, damp, a wet laundry feeling. Whereas in spring, it's really refreshing. Everyone wants to read into the record, like "Bradford's happy now!" but, like, let's just take it as a physical thing. Can't we just talk about the weather? The weather was really pleasant when we made it, and we got to experience a lot of daylight hours, which was the complete opposite of Monomania. Recording Monomania was perhaps one of the unhealthiest experiences of my life. It was just a record of utter pitch-black darkness. Just dark, dark, dark. I'm not just talking emotionally or psychologically.

Did you consciously decide to avoid doing anything like that again?

I don't think anyone in the band could survive doing that again. It was almost hexan, or like witchcraft or black arts. It was hyper-magnetic and draining, like some kind of perverted alchemy. I know to most people it just sounds like a garage rock record, but it was very cathartic. I recently found this hard drive — we had filmed the entire recording sessions with a friend of mine in a home video kind of way. I was looking at the footage and I was just like, "Jesus, I look like a walking corpse!" It's not like I'm so much happier now, but like, damn, anything would be an improvement.

When I say "black arts," I am not being funny or referring to Satan or some conservative historical view of the black arts as an actual terminology for witchcraft. It's just the forms of art that are, I don't know, more…primal. Patti Smith, I think, is a practitioner of dark art. John Coltrane, in his later period in life, like Interstellar Space, that's definitely a record of black art. A Romanian composer like György Ligeti, that's very much black art. I think that someone that practices black arts isn't concerned with immediate returns, or the failure of one experiment or another. I think Radio Ethiopia is a great Patti Smith record, but I guess people were very dismissive of it, and commercially it was a disappointment. I like to think that maybe Monomania is a Radio Ethiopia for us. It was vital, the message was intact, but it didn't really float with people. But it doesn't make it any less special. It wasn't a comfortable record to make and I don't look back fondly on making it. It gives me the heebie-jeebies, frankly. It was just witchcraft. That's just where it came from. I had no control over it; I don't like that kind of thing.

Do you carry those associations over to when you play those songs live?

BC: The Monomania tour was very dark and any kind of humor was sinister, you know. I was in a zone. I would like to say that zone is gone. That was very much, here's just the dark part of me. It's not an act. I don't take it too seriously, it's not high art, but it was an exorcism.

Do you think anyone else right now is making "black arts" music?

BC: Last night I thought about Patti Smith at her peak, and the vitality of her, and engaging with dangerous music. I used to be a sort of frightening figure, just aesthetically. A stark, bony, sickly figure, and I had all this feedback and noise behind me. I was very theatrical, and it was vital because I was just screaming about hopeless concepts. Whereas now I'm just too tired and too old and unexpectedly and unwantedly sort of bourgeois. I can't pretend to be a 19-year-old with all the anger in the world, or a 23-year-old reading Jean Genet and thinking about having a staring contest with death or something. I'm at the point where I have a less vital message, and that's just part of getting older. I guess that's why people lose a certain relevance, and people always prefer earlier records. When I listen to this record I don't hear that sinister, scary vitality. But then again, I'm not fucking 23 years old. But you know, the sad thing is that I don't think there's any 23-year-olds right now doing what we did, or what many bands before us inspired us to do.

I have no interest, or I'm not educated enough about exactly what's going on. And I'm sure a lot of people would be like, "There it is, you just don't know." Well, what I'm saying is this: We were very lucky because we were some kind of transgressive band that got more attention than is normal, and certainly more than expected. Are there any bands like that now? What's going on that's vital? I'm certainly wouldn't say we are. This has nothing to do with me — I'm speaking entirely outside myself as a fan and observer. It seems like Death Grips might really be going into this area, but I still haven't had a chance to see them and I don't know exactly what they're doing. It's hard to understand and I think they want it that way; they're embracing this…cult, or occult, militarism. Secret society weirdness vibe. I think their music has some interesting shock and awe to it. Those guys aren't fucking around, they're not playing. If we're being specific, white music is banal as ever. It's just like artificial flavoring at this point, just nothing. It's just a memory of a half-forgotten nostalgic drum sound.

Before I get called out on hypocrisy, because maybe I use nostalgic sounds here and there, but when I go on a nostalgia trip it's not aesthetic. For me it's about trying to recapture the smell or the feeling of something that I've experienced in the past personally. Like, Athens, Georgia, in 1987. I know what it smells like, I know what it sounded and felt like. I try to recapture, as an experiment, to see if I can go to a new place in the present time from there, if that makes any sense whatsoever. It's like time travel. But today I see a lot of people doing an "'80s thing" who weren't even born until the '90s. I'm not trying to be overly critical or cynical.

It seems like a lot of what you value comes from older artists who've made a lot of work.

BC: I'd say that most of my favorite artists are not young, and in my theory of art, they were never young. They were always old souls, you know, like Leonard Cohen.

You've got Tim Gane on this record, and I think Stereolab is a good example of that.

BC: Stereolab, right, no question. I think Broadcast was too. I don't understand how culture ignores them. I don't understand the relevancy game, and I could give a flying fuck how many hits something gets. It sickens me. I don't want to sound like an elitist, but it feels like they're being forgotten. Broadcast were never acknowledged in their lifetime. I look at Deerhunter and what we've gotten to do, and I look at Broadcast who were a far superior band, and it makes no sense to me. It kinda ruins it for me, you know? If you ever needed to know that talent and making something truly beautiful or whatever, it doesn't amount to anything or guarantee recognition; they're a great example. It's made me cynical at a young age to see how overlooked certain groups I've admired are.

Is putting Tim from Stereolab and James Cargill from Broadcast on the new record your way of putting them out there?

BC: All I was thinking at the time was what would sound really good on this would be Tim's electric harpsichord; or on "Take Care," this really needs a certain kind of noise that I could handle arbitrarily as just noise, but James from Broadcast is like the Michelangelo of noise. He makes breathtaking Renaissance art out of static and distortion. It's truly Baroque, you know? It was less of a move, but more like "this record needs this noise, it needs this texture," and luckily I knew just the right people.

That kind of co-sign matters. Your younger fans can find out about them through your records.

BC: My entire education in music was in reading interviews with bands like Stereolab and finding out about Brazilian music or a Romanian composer. You expose yourself to what people you look up to admire. "If he eats Wheaties, maybe I can be like him if I eat Wheaties." I don't think anyone doesn't go through that, to an extent. That's what culture is based on, the passing down of a certain narrative by imitation.

When did you make Fading Frontier?

BC: It was made in May, I think. I don't like to fuck around. I'm not a fan of holding on to a record for a long time unless it's something I want to do, like a scheduling situation that I can't avoid. I want the music to be heard as close to when I made it, as much as possible. I don't want to get into some "future of the music industry" thing, or where I stand on digital this or that, but I think it's ridiculous that a lot of people in the industry plan so far ahead that it makes a lot of improvisation impossible and makes a lot of people's expectations fixed and not fluid. Things just feel regimented in a way that art is not supposed to be. You have to book a show a year in advance now. How are you going to know if you'll be putting on the best show for people a year from now? By that time you might already be sick of the music, and you've moved on to some new music but you're playing an uninspired show and the audience paid a lot of money to see you play. My main goal in life, and this is the truth, is to make people — I don't want to say happy…

Satisfied?

BC: I want to satisfy the listener, exactly. I want to entertain the audience. I want the people to leave the show with the feeling I used to leave shows with when I was young, and I couldn't get over it for another three or four days after it. I just kept reliving the set in my mind. That hasn't happened to me in maybe 10 years.

What was the last thing you remember doing that for you?

BC: Liars, on the Drum's Not Dead tour, were the last major arc of my musical experience, I guess. That was a band that was completely involved in something I don't really understand, some kind of transcendental transaction. They were on a precipice, you know? I've never seen a band like that since. I've never seen a band come close. And there was humor to it too; it wasn't like going to see Einstürzende Neubauten. Well, I guess there's humor in Einstürzende Neubauten, but a certain smug humor. Liars had charisma and personality.

How prolific are you lately? You went through a phase of releasing so much music in Deerhunter and as Atlas Sound, but it's slowed down a bit.

BC: Honestly, that prolific era is definitely slowing down. You can only say the same kind of thing a certain number of times and then you start thinking, "I want to think about something something else, I want to move on, I want to be non-linear." And then you think, what does that mean? I refuse to put myself into a situation in which I have to face some kind of "I'm losing it" kind of thing. I'm not "losing it"; it's changed. What it is is changing.

Do you spend more time on the songs now?

BC: I wouldn't say that's true at all. I have the same writing process I've always had. You know what it is, probably more than anything? I used to be a lot more engaged on an improvisational level than other people. I was always on tour and always had a guitar in my hands, and when I went back home, my battery was at full charge. I had a lot of energy to get off, just impulses that I could draw upon. I'm still constantly picking up the guitar or playing an instrument, but there's not as much for me to say. I don't think you should make music to make music, just to show that you can. That's the opposite of vitality. Those things always have to sound and feel like they had to be done, like them or not.

This interview is condensed quite a bit from a nearly three-hour conversation full of interesting off-the-record tangents. Sorry you have to miss out on some fun stuff, but if you're hungry for more off-the-cuff Bradford chatter, you should go see Deerhunter and Atlas Sound on tour together this winter.

I used to run into him all the time out and about at shows, but it's been years. DH's last record was one of my favorites. In a bit of synchronicity I was listening to a bootleg of an Atlas Sound live show from the Bell House when I saw your email. Some pics from the last time I saw him live - https://www.flickr.com/photos/johnmcnicholas/albums/72157646854761645/